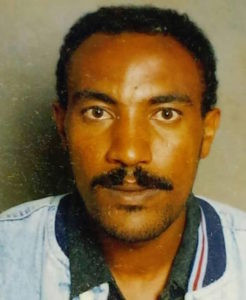

➣ Learn more about Furkan our Empty Chair file and on PEN International's statement.

➣Despite his imprisonment, Furkan courageously continues his journalism and reporting on abuses on his X (Formerly Twitter)account

➣The stories are originally written in Turkish and published on Furkan's X(Formerly Twitter) Account

➣Translated with the author's consent by PEN International Board Member Ege Dündar

➣Publishing supported by Swedish PEN in collaboration with PEN Opp Magazine.

PART 1 - PRISON DOESN’T LIKE HEALTHY PRISONERS

Prisons don't want strong prisoners. Prison floors are slippery; one must be careful at all times, thinking about every step taken. Whether sitting on a chair, pacing, or eating, prisoners must never forget they are in prison. Prisoners don't even have clean water; as a method of reform, the state forces them to wash with water reused from sewage. Everyone accepts it, but the body does not. The descendants of those who ruled continents force upon us all that the human body rejects. A journalist dressed in sparkling clothes on television started talking about our mighty UAVs and SİHA drones. I writhed in pain, the hatred of millions between my teeth. “Turkey's progress and leadership continue in every field,” said the journalist on television. I reached for my kneecap, pulled up my sweatpants, and ripped my crusted wound open in one go. I raise my head to the sky, thinking maybe the UAV of the state that gives its citizens dirty water would pass overhead, though I saw nothing but gray clouds.

“Roll call, gentlemen!” the guards called. Dozens of prisoners took their places in the courtyard, staring at the concrete floor. They started shouting in the corridor: “Attention, the lines will be counted.” They thought they were having fun, as if this were a barracks, they were the commanders, and we were the foot soldiers. Suddenly, the guards flooded into the courtyard. “Peace be upon you!” “One, two,” the imprisoned began counting themselves. The senior guard, who thought he was the commander, stood with his hands tied behind his back, trying to catch the prisoners' eyes. The guards went inside and started searching as they pleased. They cut and removed: the extension cables we had made for our radios, the antennas for expanded reach , the curtains we had made for the bunk beds, the ropes. With every sound of something being torn down, a scab broke off from my wounds. The prisoners, their brows furrowed, began to avert their eyes, which held disappointment mixed with hatred, sadness mixed with weariness. “Get out of there, take those bottles too,” the senior guard, who was not the commander, began to shout. The guards took everything we had made to improve this place, such as the dumbbells we had made by filling bottles with water, then they left, saying, “May God save you.”

They don't want prisoners to exercise because then they would become healthy and strong. They don't want them to put up antennas and listen to different music because then they would be happy. They don't want us to lean on each other because we would get agency. For them, the ideal prisoner is the weak, sick, and needy one. Like voters, you see. The door closed, and the prisoners rushed in to tidy up the cells. Ropes were pulled out, ropes were made, curtains were drawn, wires were pulled, and the radio was turned on. “Come tomorrow, tear it all down, carry it away and we'll set it all up again tomorrow.”

PART 2 – I WILL NEVER FORGET YOU, I WILL IMMORTALIZE YOU

For the morning roll call, the prisoners tucked their chins into their sweatshirts and stepped out into the courtyard one by one, shivering. Dozens of us lined up in a U-formation and waited for the guards in the rain. The cold air and rain drew us closer together. Shoulders rubbed against each other, sharing both loneliness and warmth. The guards, who came to the roll call with the air of commanders, cut the ropes and then slammed the door in our faces once more, like victorious soldiers, with their chins up, saying, “May God save you.” “May God save YOU,” I whispered, squeezing in next to Uncle Toso

Uncle Toso, slowly pulling on the heaviest rosary bead in the cell with his left hand, took a drag from the cigarette in his right hand and said, "Look, my dear, one day this door will open for all of us, alive or dead. What matters is not how we got in here, but how we get out. Those who leave here are remembered either for their deeds or their mothers.“ "Isn't this the only thing befitting a mortal a life of honour, Uncle?" I lit my first cigarette of the day, filling my lungs, and took quick puffs. I passed through the prisoners preparing their breakfast with blank faces, quickly turning my prayer beads. “The hatch is open, Teacher*, they're calling you, go see the guard.” I jumped out of bed and leaned over the hatch, and two clean-faced guards smiled, “Get ready, you're being transferred.” The news of the transfer instantly reached all the cells in the dormitory.

To send me off, some brought the cake they had been saving for weeks for a good movie, while others brought the chips and drinks they had been saving for the Champions League, and they filled the bag that had been prepared for me to take. Within five minutes, my belongings and provisions were ready. I made eye contact with the President*, who said, “Wow, Doctor*, they're sending you away, but once we love someone, we never let them go.” I climbed the stairs two at a time, passing the young people who wanted to say goodbye, and found Abdulhalit. I hugged Abdülhalit without feeling my arms, and he said, “Teacher*, don't leave us, don't go, don't let them take you away.”

Not a single word came out of my mouth. I couldn't feel my arms, I couldn't let go of Abdulhalit, I don't think I've ever hugged any of my relatives like that. You're a drug lord, Abdulhalit, but you're like a father to me. He said, without losing his smile: “Our best days were spent in prison. Our child grew up, but we didn’t see him grow up. He went to university, but we didn’t see that. We won’t see him get married either.” When you start living outside, you start to break down. Abdülhalit has recently started living outside. It's not just Abdülhalit; when one person starts living with the outside world, this feeling spreads to those around him. It's easy to say, but some have five years ahead of them, some have 15. When you're outside, you say, “Let the guilty serve their time.” Of course, it's easy to say this until the prisoner is you.

Uncle Toso jumped out of bed in a hurry, reached into his pocket, and thrust the folded paper into my hand. Speedy watched me from the corner with his eyes that could hold all emotions at once—angry, sad, shy. We hugged, and he said, “We'll meet on the outside, brother.” I dropped the prayer beads in my hand, whispered, “Give this to Orthodox Aslan,” and headed for the door, whispering “May God reward you” to those lined up on the stairs. Eser was waiting with compassion in his eyes. He hugged me, kissed my shoulder, and said, “Keep going, we're behind you.” The President* roared at that moment, “Doctor!*” We hugged, and I looked into the shining eyes of Uncle Toso at the door, saying, “Give my regards to the boss.” I stepped through the door, turned around, and saw the prisoners with broken hearts, calloused hands, and stiff, upright backs. I said to myself: “I will not forget you; I will immortalize you...

PART 3- WHAT ARE YOU DOING HERE?

The iron gate at the end of my bed opened. “You have a court hearing. Are you ready?” “I'm ready, I'm ready. I don't know if they're ready, but we'll see when we get there.” I took three cigarettes with me, thinking we could light them if we found a lighter in the courthouse. “Are you taking your files with you?” asked the guard. “No,” I said dismissively. What would I do with the files anyway? They'd just give me the maximum sentence, and I'd end up back in prison, wouldn't I?

Looking at their faces, it was clear that most of the prisoners were from prison number 3. There are 10 different prisons in Silivri, the purpose being to separate prisoners according to the type of crime they committed: drugs, assault, theft, weapons, terrorism, organized crime, and so on each has its own “number.” We arrived at the 7th floor of the Çağlayan Courthouse. Courthouse detention centres are places where detainees socialize. Some wait for their accomplices, some wait for their enemies, and some bring greetings and deliver messages. Thirty or forty detainees were locked behind iron bars, everyone sizing each other up with their eyes, wondering, “Is my enemy here?” It was a chaotic time, and they didn't know if a gang of two or three young men they had never met before had declared themselves their enemies. But prisoners need other prisoners, and no one knows this better than themselves.

There were cigarettes, but no lighters. Everyone was waiting for the first move, not wanting to be the first to show they had a cigarette or a lighter, until a prisoner in the corner of the toilet pulled out his cigarette and lit it as if he were on the beach. The guards were lowered, the curtains were down, and those with cigarettes went to the corner and started offering them to those without, as if they were 40-year-long friends. Just then, the gendarmeries came in and collected the cigarettes. The last time I had passed a cigarette around quickly was in high school. “Where are you from?” “Number 9.” “Oh my God, aren't the arrested mayors there too?” “Yes.” “What do you do?” “I'm a journalist.” “How old are you?” “29.” “Are you married?” “No.” “Where do you live?” “Man, you're asking questions like I'm being interrogated.” “I don't know, you're answering so quickly, so I'm just asking whatever comes to mind.” I started laughing.

Someone who heard “No. 9” came over to us, saying “Is it good to be alone? You'd go crazy in there,” “Is there a TV?”, “You'd lose your mind without talking,” “Have you seen the detained mayors?” The detention centre was filled with smoke, some from cigarette butts, some from drugs, some from gambling gangs. Their common sentiment was, “We get why we are here but journalists, mayors, congressman, academics, what are you all doing in jail?”

PART 4- The Prison Psychologist

The grate of my solitary cell opened, and in two steps I was at the foot of the iron door. A familiar face greeted my eyes: “Why did you come again, welcome back.” “Nice to see you, are you okay?” “I'm fine, I'm fine, why did you come again?” “Why else would I come? Journalism.” “Get ready, let's go to the infirmary.” I put on my white shoes, which always made me feel comfortable, and left the cell. If only I had my leather jacket, but I don't because leather is prohibited in prison. We climbed the stairs and started waiting in front of the infirmary door. We were going through the same rituals, in the same place, with the same people. It doesn't matter. Inside or outside, it doesn't matter; isn't life just a series of repetitions anyway?

As soon as I entered, I saw another familiar face: “Hey, you're here again.” “The outside is terrible. What were we going to do?” My prison routine was filled with short, carefree, effortless conversations like those during holiday visits. “Come on, go see the prison psychologist and get it over with.” “Sure, bro.”

The psychologist's office is my least favourite place in prison. Questions asked for the sake of asking, answers given just to get it over with, dancing around each other. “Doc, I brought you our regular customer,” he said, knowing I didn't doubt his sincerity. I sat down on the chair, and as I hadn't sat on a cushioned chair in a long time, I decided to prolong the examination.

“Have you ever had an unforgettable event from the past that shook you, that saddened you?” “Of course, like every human being, I have had my share of saddening deaths.” I wanted to extend the conversation, but I couldn't. Who in life hasn't been shaken by death, hasn't grieved? Yes, sir, there are deaths I can't forget, deaths that make me want to grind my teeth in anger. I can't forget the poor children who burned to death in a shack, those who died in prison on hunger strike, those killed by police violence on the streets, those tortured to death by the state behind four walls. Do you think we should forget? I answered the questions straightforwardly, without elaborating, and left the room to go to my cell and light a cigarette. As I walked out with the guard, I heard the slogans of the revolutionaries from Block C. “I missed the sound of slogans,” I said, and my escort laughed.

Part 5- The Need to Do One More Thing

I have things to tell, things to shout about, things I need to make heard. I must write, I must report, right now. My breath is failing me, my words are not enough, my pen does not pierce their throats deeply enough. I need to do something more, something else—news, stories, essays, defences aren't enough. I need something more, not to extinguish the fire but to fan the flames—something more, a story, news, a book... It's not enough, I need something more.

“If only I could pour out what I'm thinking right now, what's going through my mind, what I haven't written yet,” I said to myself, pulling the rosary beads my brother, who is as much a father to me as my own father, had brought me, two by two. I didn't know how many minutes the rosary beads had been in my hand as I pulled them hard and fast, as if breaking the amber stones. I opened the window of my cell and lit a cigarette, drowning out the foul smell coming from the drain in the courtyard with smoke. I came across Evanescence's song on TV. “Where did this come from?” I said. I must have last listened to it in high school. At least there was an electric guitar; even hearing its sound was nice. Although I found it too naive and soft for a metalhead, I listened to the song “Bring Me to Life,” which everyone knows in some way... I clenched my teeth, scribbled my romantic lines, and quickly wound the prayer beads around my finger.

I thought about the news stories I had to write about, picking at the scab on my ear. I had to not only pick at the scab, but also to get rid of it. Who will do it? We will, of course. We are not, and will never be, the kind of people who wait for someone else to do something and then pass away. “Peace be upon you,” came a voice from the corridor. It was conversation time in the corridor, where seven cells stood side by side. I got up from my chair, spread the black trash bag in front of the iron door, and lay down on it to hear better. There is a small gap under the heavy iron door that separates you from life in the other cells. That gap connects you to the outside, to life itself.

Translated with the author's consent by Ege Dündar.

*:nickname

*Supported by a joint translation and publication effort with Swedish PEN and PEN Opp Magazine.

*You can write a support letter or postcard to Furkan Karabay using the address below:

Marmara Cezaevi Kapalı Ceza İnfaz Kurumu A/80 Koğuşu, Silivri/İstanbul, 34570